Remembering Joe Stamey

(If you’re here to read about Joe Stamey, and don’t care much about how I came to know him, skip ahead to the horizontal rule.)

I’m embarrassed to say that I’m a bit proud of the fact that I was one of Richard Nixon’s mistakes. Not a very significant mistake among other mistakes (and misdeeds). In 1971 I received a Presidential Appointment to the US Military Academy at West Point. I came to see accepting that appointment as a mistake pretty quickly – I was there only for 8 weeks, so I’m convinced that Nixon would have agreed – but my being there changed my life. In fact, when people who’ve met me since then tell me that they can’t imagine me going to West Point, I tell them that one reason for that is the fact that I went to West Point. (Though, to be fair, there were those who knew me before I went who have said they thought it would never work out.) One decision I made during my time at West Point stands as a good indicator of how my experience changed me: I decided that I wanted to major in philosophy rather than physics, math, or engineering.

After leaving the academy, I went to McMurry, a small, regional liberal arts college in Abilene, Texas. (I graduated from high school in Germany, but I was a native Texan.) I saw McMurry as a transitional place for me, thinking that I would transfer to another college. But that began to change with I met with Joe Stamey, a philosophy professor who became my academic advisor. It was clear to me pretty quickly that Joe (or, as I called him then, Dr. Stamey) was very bright and well-read. But my experience of him in my first philosophy course – a junior level seminar in modern philosophy – quickly convinced me that it was very unlikely that I could have found a better teacher and scholar. So I stayed at McMurry.

(Yes, I know. I’ve now worked with enough philosophy professors at enough universities to know that I could have received a solid education in philosophy elsewhere, but I remain convinced that I couldn’t have studied with a better philosopher and teacher.)

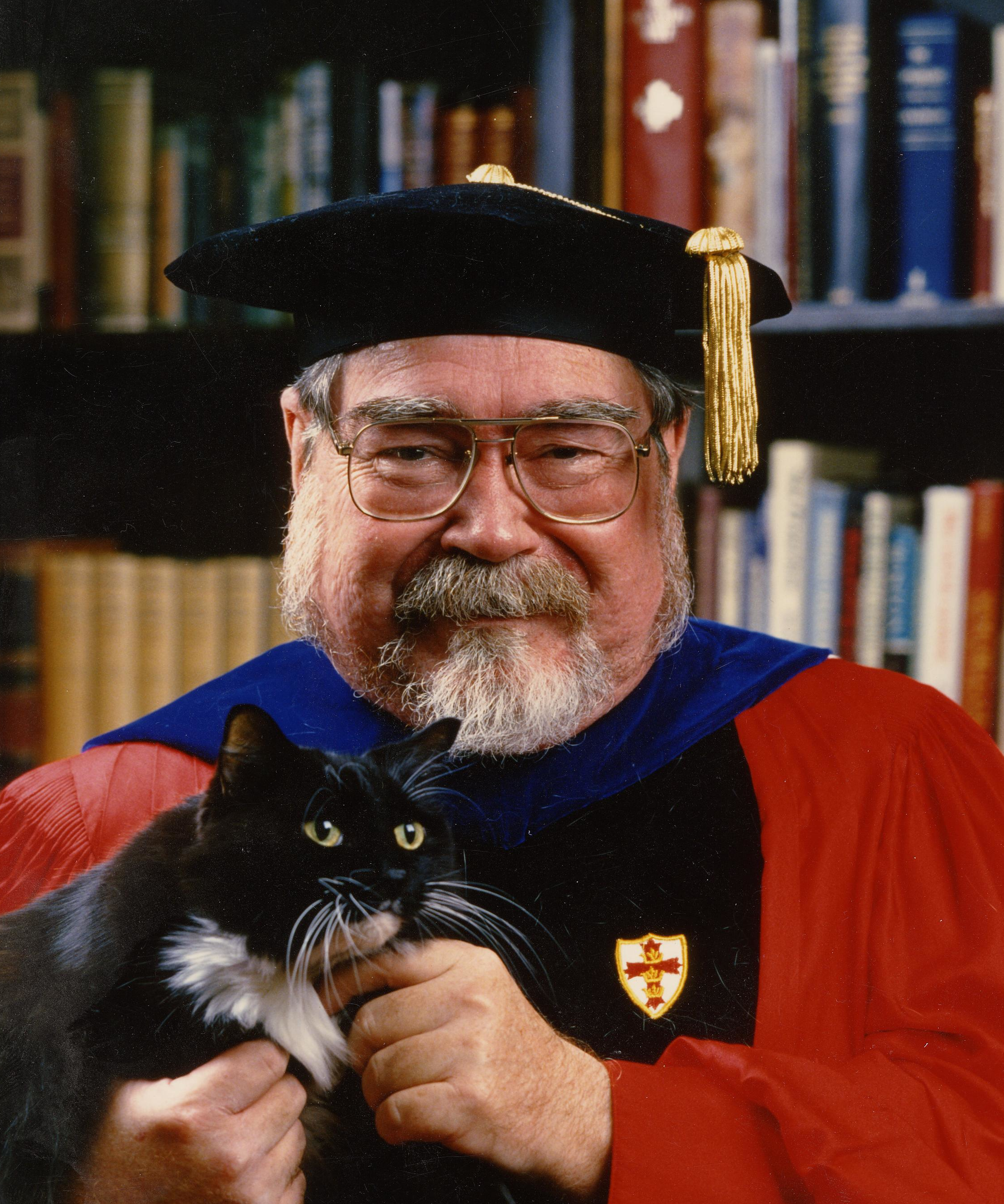

All of this is on my mind now because I just returned from Abilene – my first time there in decades – where I spoke at an event honoring Joe and the contributions he made to McMurry. I’m honored to have received the invitation to speak. Here’s what I had to say in the three (or so) minutes that they gave me.

One of the big challenges we face these days, I think, is making room for wonder in our lives. Just begin a sentence with the words “I wonder…” Someone quickly pulls out a phone or tablet, saying, “Here, I’ll look that up for you.”

This comes to mind today because I learned about the power of wonder from Joe Stamey. He introduced me to many different philosophers. One of those philosophers is Aristotle, who in the opening pages of his Metaphysics said “philosophy begins in wonder.” Joe lived his life wondering about things. Of course I’ve known that for years, but I know it even better now. In the past few months I’ve resurfaced memories of my time with him, and I’ve also made my way through a stack of papers that he sent me over the years, reading through much of what he wrote – a lot of it unpublished. One thing that stands out in these writings is just how broadly and deeply he read. Again, I knew that already, but still. It reminded me of the time that McMurry’s head librarian put out a call to all faculty to please return the library books that they were hoarding on their shelves. Joe obligingly returned something like 500 books, but he told the librarian that he simply couldn’t return the other 100 because he was actively using them.

His wondering played out in his life, not just in his scholarly papers. He worked with Bob Monk and other colleagues to write introductory textbooks. He wondered how Bob would react if a collection of small animals like this one showed up on his desk. (I don’t remember whether Joe or Bob gave this to me, but I do remember Joe telling me slyly that Bob didn’t know he was doing it and Bob telling me matter-of-factly that Joe was putting them there.) At a departmental holiday party, I watched Joe, standing by himself in the corner of the living room, pull a small notebook out of his shirt pocket and write a note to himself. Maybe he was adding an item to a grocery list, but I don’t think so.

He wondered out loud in the classroom, asking his own questions about the texts we were reading and also drawing questions and comments out of those of us barely able to make our way into these texts that he knew so well. I could say so much about his teaching practice, but I’m going to turn instead to the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s comment on respectful criticism.

We have “a duty [Kant says] to respect a human being even in the logical use of his reason, a duty not to censure his errors by calling them absurdities, poor judgment, and so forth, but rather to suppose that his judgment must yet contain some truth and to seek this out, uncovering, at the same time, the deceptive illusion, and so, by explaining to him the possibility of his having erred, to preserve his respect for his own understanding” (Metaphysics of Morals, 6:463).

Time and time again in Joe’s class, I watched as he responded to a student’s ill-formed question or comment in a way that captured the gem expressed there. He helped to shape an environment in which our uninformed wanderings became fascinating wonderings.

Finally, I come to the philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead – another whom I read first with Joe–who made it clear that the wondering doesn’t stop. “Philosophy begins in wonder. And, at the end, when philosophic thought has done its best, the wonder remains.” Joe lived with his wonder throughout his life – in the classroom, in his writings, and in day-to-day conversations. There was a time at McMurry when I looked across a seminar table at Joe and thought “I’d like to be you when I grow up.” I hope that I’ve managed to show here just why I couldn’t possibly be the person and philosopher that Joe was, but I thank him for inviting me into a life of philosophical wonder.