The Connections of Music, With Strings Attached

I don’t play guitar all that much anymore, though I’m trying very hard (or, at least thinking very hard about trying very hard!) to develop those fingertip callouses again. Though I don’t play much, I still treasure the guitars that I own.

But one of those guitars — an old Guild D35 acoustic — feels rather special these days. It’s had quite the life.

In the mid-1970s, when I was a graduate student in Texas and had virtually no money, I was visiting my family in New York City. My younger brother, also a guitarist, took me with him to one of his favorite guitar stores. I wish one of us could remember the name or location of the store – if it still exists, I’d like to visit it again. As I said, I had very little money to spend, and I really didn’t intend to buy a guitar. I was just there to look around, I told myself. But, of course, when one is in a guitar store, “looking around” also means “playing around,” and soon I was strumming a few chords on that Guild guitar. I really don’t remember how, but somehow I scrounged up enough money to walk out of that shop with that guitar. It was my first decent six-string guitar. I played it as best I could for six years or so.

Sometime around 1980 I was on leave from graduate school, working a job where I had a bit more money. I made a mistake somewhat like the one I made in New York City; this time a good friend living in Albuquerque took me to a luthier’s workshop up in the hills east of the city. We spent several hours there – and against my better judgment I found myself selecting the wood for a guitar top, sides, and neck. About six weeks later I received those pieces of wood in the shape and form of a guitar. I’m ashamed to say that I ignored the Guild for a while.

My leave ended, and I returned to graduate school. While I was away, a student named Jerry had come to that university. More than a few friends told me that I really should meet Jerry. As I recall, I didn’t meet him until he showed up at one of our regular singing and picking parties. He was one of the pickers. I don’t remember which one of us picked the first song, but we were hardly into the first verse of one of the Crosby, Stills, and Nash classics when I began to realize just why those friends had told me that I should connect with Jerry.

The connection based on playing and singing together grew into a connection based on all sorts of things, many of them music oriented. A few years later we spent a long weekend at the Kerrville Folk Festival. Sometime before or after that weekend Jerry expressed an interest in purchasing the Guild guitar. I was happy to see it go into his hands, and we consummated the deal.

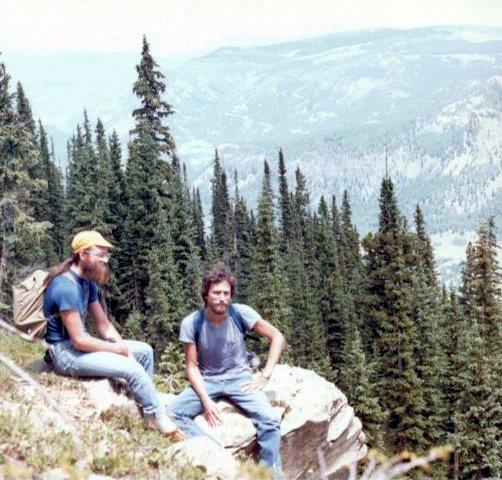

Jerry finished his studies and moved home to Nebraska. I visited him in Lincoln a time or two while I was still in school. We met in the Colorado Rockies for a week of hiking and playing. Jerry’s on the left in the picture of us as resting a bit while making our way up a rather steep trail to the top of a mountain. On the way up, we had to step off the trail for a few minutes so that a group of people on horseback could get past us. Jerry’s comment: “I suspect those horses are going to have a great sense of accomplishment when they reach the top.”

A few years later, Jerry returned to Dallas for my wedding. Of course he brought the Guild with him, and we had another wonderful night of playing and singing together at the party the night before the wedding.

Then, sadly, we lost touch with each other. Jerry stayed in Lincoln, making his way as an outside artist. The video linked on that page holds a lesson that still challenges me: “You gotta feel the freedom to screw up, and know that you’re a screw-up, just like all the other screw-ups that are walking this earth; but, wouldn’t you rather be a screw-up, that expresses yourself, than a screw-up who is afraid to do anything?” Maybe I’d be different now if we’d still been together so he could have said that to my face. (Or maybe he did, and I just wasn’t able to hear it.)

Sometime around 2006, we reconnected on Facebook. His posts reminded of his wit and his music. He and his wife visited us in Virginia when she had a conference in DC. I visited them in Lincoln when I had a conference at the university there. In one of those conversations, I mentioned that I regretted having sold him that guitar, and asked if he’d be willing to sell it back to me. “No,” he smiled. “A deal’s a deal.” He let me play it for a minute, but insisted that I leave it in his care.

Not long after my time in Lincoln, he messaged me with some really bad news. Not one to beat around the bush, he got straight to the point. “John, I’m dying. But I want you to have this guitar.” I was dumbstruck – Jerry was a young man, two years younger than I was, but his esophageal cancer was diagnosed too late. He died in February 2013, less than a month after sending me that message. In just a couple of weeks, he’ll have been gone a dozen years.

Several years after he died, I received a message from his wife. “Jerry wanted you to have this guitar. Can I ship it to you?” Of course I said she could. A month or so later I took the guitar out of the case here in Boston. I played it a bit. Even though the strings were at least 10 years old, it felt right, having it pass from Jerry’s hands into mine. This past summer, I dropped the guitar off at 30th Street Guitars. They checked it out, did a basic set-up, and replaced the strings. When I went to the store to pick it up, the owner brought it out to me, strummed a few chords, and told me that I own a treasure.

Yes, I do. But the treasure is more in the knowledge that Jerry played it for over 40 years than in the guitar itself. Playing it now, knowing that he played it for decades, brings back so many memories of sitting across the room from him, seeing the glint in his eye as he added a particularly striking harmony. As archaeologist Christina Riggs said in a rather different context, “A guitar is only a guitar, if you do not know who brought its strings to life.” Jerry brought these strings to life, and offered the gift of the life he created with it to others. His death left a huge hole in my life, unfilled even after 12 years, but I gain some comfort in my connection with him via six metal strings attached to a box of wood.